Brilliant the Basics: genAI as a catalyst, not a silver bullet for improving education.

Given the spread of unsupported claims by officials and self-anointed pundits there is need for changes in how science is taught and understood. genAI tools can catalyze these institutional changes.

Reflections: After retiring as a professor in June 2025, I have time to reflect back on various aspects of the college education industry. I was thrown into the instructional/educational caldron soon after my arrival in Boulder, Colorado about 42 years ago. I was assigned to teach a large required course in Cell Biology. While at the time my research work involved cells, I was otherwise unprepared, untrained, and naive when it came to teaching - the types of topics one or more School of Education courses might have helped me develop; the type of background a typical middle/high school teacher would be expected to have. I also did not appreciate, nor had reflected upon the impact of a number of common practices - such as "curving" exam scores, the use of multiple choice questions, or even how to design questions that provide objective grounds to evaluate student mastery of key facts and concepts, questions needed to know whether a student had learned would I expected them to have learned.

Over the decades, through the experience of teaching college courses at all levels, and invaluable interactions with a number of collaborators and colleagues in our School of Education, with expertise in the evaluation of student thinking and learning, I found myself thinking and acting differently in the classroom. In particular, I found myself increasingly aware of how the expectations of a course in terms of what students can be expected to have learned has changed; all too often courses purport to deliver over-ambitious outcomes, something that can make real learning essentially impossible for students. My own experience with undergraduate organic chemistry continues to traumatize me! At the same time my world view had been changing and had become somewhat cynical. It often seemed to me that the college educational experience was more about sorting students than teaching, an approach that has a number of negative effects on students.

While there is a common view that college education, particularly at the introductory level, involves the pundit in the pulpit. Sadly, there is little evidence that listening to lectures lead to learning. While there are recent claims of new pedagogical paradigms, the fact is that all real learning of non-trivial topics is active on the part of the student; it involves what are known as formative activities - basically practice in analyzing a problem, identifying the relevant facts and ideas involved, and the generation of plausible mechanisms to explain the phenomena. For many topics attaining true understanding is inherently hard, since often scientific principles are counter-intuitive. An integral part of this process is to present your solution for critique - does it make sense? does it make needed (or unwarranted) assumptions? (summarized here). This is a learning (ungraded) formative process and distinct from what are known as summative assessments - the tests used to determine grades. It seems that Socrates (~469-399 BCE) got the core elements of effective education right - to know, and answer questions, on a topic well enough to be able to apply one's knowledge effectively as well as recognizing whether a question is unanswerable without more information is a skill not always achieved through conventional courses. For various reasons, we seem to have forgotten much of the Socratic message.

But it is not enough to "embrace" the active, engaged nature of student learning - we have to provide students with a course environment focused on meaningful and useful learning objectives. All too often, students are presented with memorizable or recognizable "tasks" through which their "learning" is to be judged and through which they are assigned grades. Yet as many have shown, all to often students can recognize the correct answers on multiple-choice tests without understanding why they are right, or how the underlying concepts can be applied to other, real life problems. The "holes" in student understanding of key, foundational concepts was driven home for me when teaching (later on) Developmental Biology, the final required biology course in our curriculum; there was a general lack of comfort in applying ideas to particular situations and building plausible (rather than correct) explanatory models, something to be expected of students in the later stages of their college careers.

Although speculative, I think that part of the problem arises from the time it takes to generate good questions and to evaluate and provide both students and instructors feedback. In large introductory courses this is a task often undertaken by graduate student "teaching assistants". A short quiz involving written out answers can take 2 to 3 days to grade (more for a longer exam). This time-delay between quiz and useful feedback is often used as a rationale in support of machine-graded multiple choice exams. Unfortunately, many multiple choice exams are poorly designed. In this area, the gold-standard involves what is known as a concept test [], such as the Force Concept Inventory (FCI) in physics; the FCI inspired our development of a structurally similar Biology Concepts Inventory (BCI) [link] [link] [link]. For such questions, the wrong answers - known as distractors, are based on research based student misconceptions about the topic. This addresses the fact that in most multiple-choice questions, the wrong answers are basically not taken seriously by students. Of course, no matter how good the distractors, the simple fact of selecting the "right answer" does not insure that the student knows why, exactly, it is right.

We are now in a position to consider how generative (often RAG-based) AI tools can catalyze a transformation of the educational system.

Suggestions to build on

Exams: Many discussions about the impacts of genAI involve students using genAI to cheat. I will not discuss these since I think they miss the mark. That said, the first step in this education reformation is to convince students that all summative assessments will be carried out in a genAI-free environment. As is the case with medical board and other professional certification exams, this may require establishing special WiFi/cell-phone free rooms, and perhaps providing students with word-processing stations to facilitate the generation of answers digitally, although advances in accurately recognizing and translating handwriting into text are already with us and likely to improve dramatically. The goal is to convince students that their grades will be based on their unassisted understanding of, and ability to accurately apply what they have learned.

As part of this focus on exams, genAI tools can be used to analyze the questions posed to insure that they are clear and unambiguous. This is something that is routine with professional exams where bad questions can be identified through various statistical tools but is often missing in college level courses due, in part, to lack of time or expertise. Using RAG-based AI systems informed on relevant disciplinary topics - bad questions can be quickly flagged, removed or revised so that they are in concert with established course and curricular learning objectives. Students, instructors, and institutions can be assured that a students' ability to answer these questions reflects a mastery of the topics involved. A need to "curve" student scores is a fire alarm for serious problems with course design, instructor competence, and/or student engagement [link] and should lead to immediate intervention.

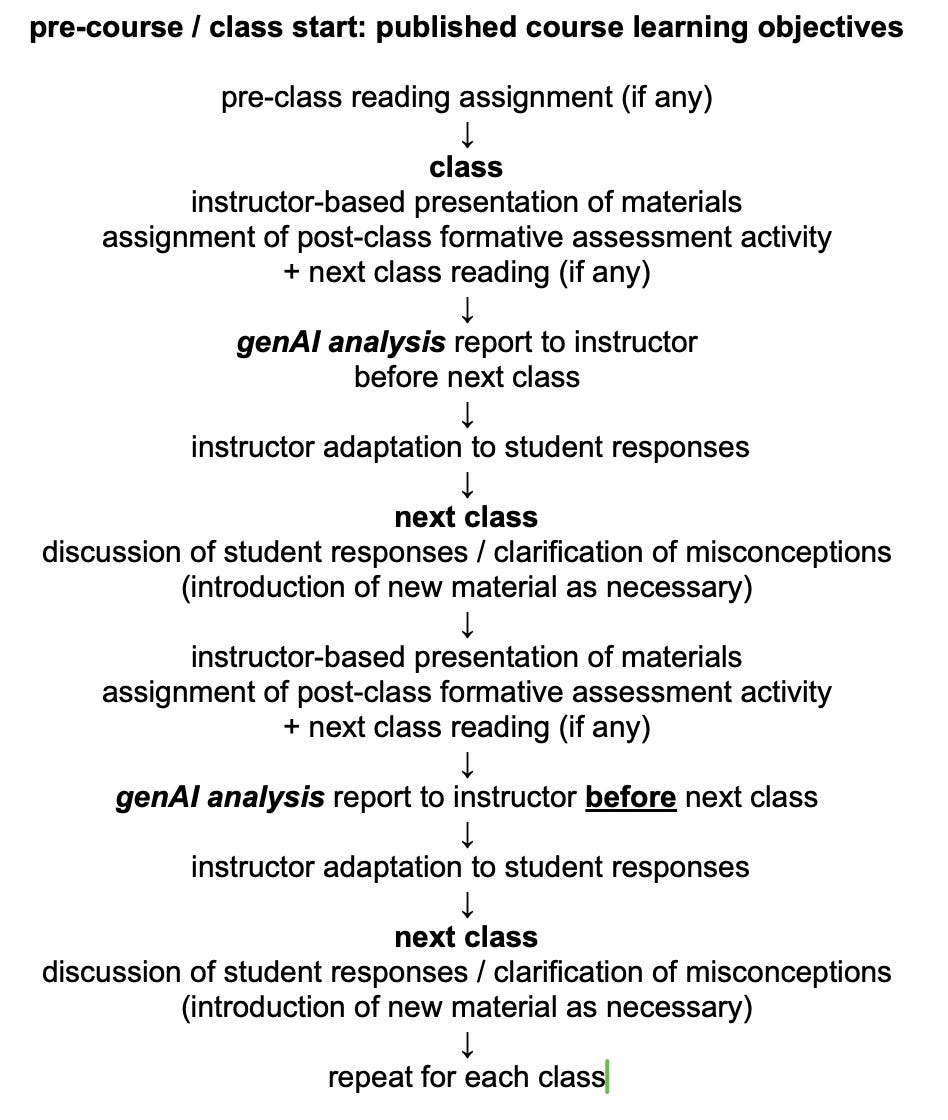

Formative assessment, feedback, and instructor adaptation: Once students accept that their summative exams provide an accurate reflection of their understanding and abilities and that they must be take in an AI-free environment, all other barriers to the use of AI should be lifted. A particularly valuable instance involves the introduction of formative assessment activities; questions and challenges that students respond to and answer for the purpose of learning rather than grading. Consider a typical situation. An instructor introduces a topic in class, perhaps based on or supported by a pre-class reading from a textbook. The instructor then assigns a formative (un-graded) assessment activity, to be completed before the next class; this activity

presents questions for students to respond to the best of their ability. In our case we use the beSocratic™ system [link] that allows for student drawings and text. In a recent upgrade, beSocratic now provides instructors with an analysis of student responses, in much the same manner as described in our arXiv paper on the analysis of multiple choice questions [link]. It identifies critical ideas left out, misunderstood, or misapplied by students, as well as misconceptions and pedagogical hints as to how to address them are forwarded to the instructor. The instructor's task is to consider how to address these issues at the start of the next class BEFORE they move on to new material. Adaptive learning strategies by the instructor requires that they have the deep understanding of the disciplinary principles involved together with the license (authority) to adapt to students' issues in terms of altering the scope and pace of their presentation of content and, if called for, to focus on foundational ideas, rather than coverage of more superficial, memorization-based course goals.

Course and curricular evaluation: Another aspect of the use of genAI is the overall evaluation of the effectiveness and relevance, of a particular course or curriculum in training students. A way to provide timely and objective evaluation of whether students (and society) are getting their moneys, time and efforts worth from a course or an educational program. This could be done simply by analyzing the summative assessments students have already taken. Such assessments could be analyzed in a temporal fashion to reveal learning with time in a program, or a specialized end of program assessment, something like a program accreditation evaluation instrument could be used. The results could provide clear evidence that the summative assessments used are able to unambiguously evaluate whether or not the stated learning objectives of a course or program are actually being met, together with an evaluation of those objectives (are they meaningful or not). Such information could be used by students to choose programs, institutions to evaluate courses and instructors, and the public to understand what experts know versus what people claim to know.

Summary: While we imagine that genAI tutors will become available, this is a trickier human-machine interaction that we will ignore. More to the point, it is irrelevant to insuring that at the end of the course or curriculum students have acquired the skills and expertise promised by a course or project in its stated learning objectives.

We imagine that instructors may, to begin with, have trouble adjusting to and effectively engaging with student difficulties, but after all Socrates was not pushing to "cover course content" but to achieve understanding, together with helping the student to develop the critical thinking skills in a topic so as to be able to realistically evaluate their own understanding of the topic, what they are sure of, what they know they do not understand, and what remains unknown. That would seem to be an outcome much to be wished for in a world full of self-anointed pundits “Full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” (Shakespeare, Macbeth (Act 5, Scene 5) and poseurs, “Empty vessels make the most noise” (a well known proverb).1

The title is a well known Navy Seal catch phrase, or so I am told by a reliable source). I now discover that the phrase is attributed to General Jim Mattis ("The first is competence. Be brilliant in the basics. Don't dabble in your job; you must master it")